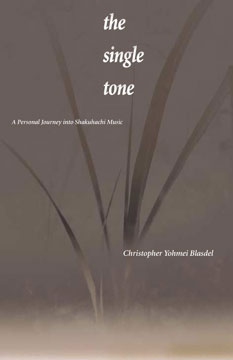

Christopher

Yohmei

Blasdel

THE

SINGLE TONE:

A Personal Journey

into

Shakuhachi Music

|

|

Christopher THE

SINGLE TONE: |

|

The long awaited English version of Shakuhachi Odyssey is finally available. The Single Tone has been re-written for English language readers with the inclusion of more materials and photographs.

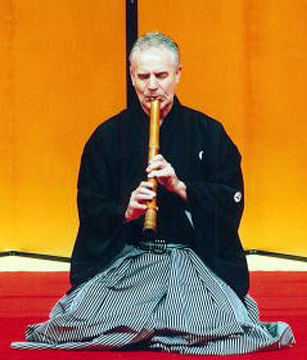

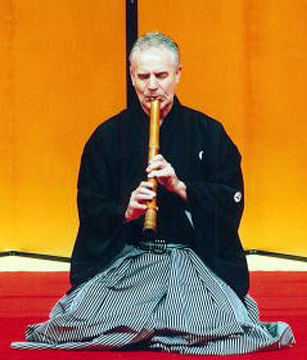

The Single Tone is the quintessential insider's view of Japan and its culture. Originally written in Japanese and the winner of the Rennyo Award for non-fiction, Christopher Yohmei Blasdel, an American who has resided in Japan since 1972, writes about his experiences studying, performing and teaching the traditional Japanese vertical shakuhachi bamboo flute. His encounters with various Japanese—from world class artists,wealthy patrons, respected scholars and arrogant diplomats—provide thoughtful insight into the Japanese mind. He also demonstrates the universal appeal of the shakuhachi by performing it around the world: in the jungles of Guatemala, in the ancient banquet halls of the Republic of Georgia and the wind swept Indian reservations of New Mexico.

167 pages. BK-13

Christopher Yohmei Blasdel, born in Texas, began the shakuhachi and studies of Japanese music in 1972 with shakuhachi master, Living National Treasure Goro Yamaguchi. He received a teaching license and the professional name "Yohmei" from Yamaguchi in 1984. At the same time, he completed graduate work in ethnomusicology at Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music. A permanent resident of Japan, he has performed, taught and lectured throughout China, Thailand, Europe, North America, Mexico, India, Malaysia and the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. He has been a visiting artist in residence at Earlham College, Richmond Indiana, guest professor at the Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, invited artist at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, resident of Centrum Arts Center and recently awarded an Asian Cultural Council grant to study the transmission of Thai traditional music. He was an executive director of the Boulder World Shakuhachi Festival 1998 and is the artistic director of the Fukuoka Gendai Hogaku Festival for contemporary Japanese music. His book, "A Shakuhachi Oddyssey," written in Japanese, is published by Kawade Shobo Shinsha and was awarded the prestigious Rennyo Award for non fiction. In his musical activities, Blasdel maintains a balance between traditional shakuhachi music, modern compositions and cross-genre work with a great variety of well-known musicians, dancers, poets, and painters, both Western and Eastern. Blasdel presently performs, teaches, and records in Japan and around the world. He works as Advisor to the Arts Program at the International House of Japan, is part-time lecturer at International Christian University and Temple University in Tokyo, teaches privately at the Asahi Culture Center in Shinjuku and writes regularly for The Japan Times. |

|

What People Say About The Single Tone

"Shakuhachi music is honest, profound and beautiful.

Blasdel has the passion and spirit that embodies these characteristics and

is a pioneerwho

faces both the Japanese and world community in order to invite others to participate

in this extraordinary music."

—Yokoyama Katsuya, shakuhachi performer, Director, International

Shakuhachi Kenshukan

"Blasdel's insights are a goldmine for cultural studies and ethnomusicological

scholars considering cross-cultural interaction and learning."

—Dr. Ricardo Trimillos, Chief of Asian Studies Program and Professor

in Ethnomusicology, University of Hawai'i at Manoa

"In The Single Tone, Blasdel explores the contradictions inherent in the

study of traditional Japanese music by an outsider. He demonstrates that humanity

superceeds even the strongest cultural barriers when philosophy and love of

music are the guides."

—Brian Ritchie, Bassist, Violent Femmes, shakuhachi performer

"Blasdel's love and passion for the shakuhachi permeate the work, but the

most interesting thing about the book are his observations on the Japanese culture."

—Asahi Shinbun newspaper,Tokyo

Donald Richie's

Review of The

Single Tone

The Japan Times - March 27, 2005

THE PATTERNS OF JAPAN: First, Stop, Look and Listen

In the summer of 1972 Christopher Blasdel first came to Japan. He was from West Texas, "a landscape dominated by strip malls, sprawling gasoline stations and gigantic billboards advertising rattlesnake meat and a free 72-ounce steak dinner to anyone who could eat it in an hour."

Even on the bus trip from Haneda into the city he was struck by both similarities and differences. A big contrariety was the intensity of Japanese space. "Space in Texas was a nuisance to overcome with wider highways, bigger cars and faster travel. Tokyo space was an exclusive commodity where every square inch throbbed with vitality. Though jumbled, everything fitted perfectly together and followed a kind of pattern."

The elucidation of this pattern became the life work of the young Texan. During this process he discovered that it was aural as well as visual. "I began to realize the value of actively listening to sounds, rather than just hearing them," and he discovered and took to heart the famous Zen dictum: "Enlightenment through the single tone." This single tone possesses, he discovered, a great range of complex, interlocking timbres. "All we had to do was quiet ourselves and listen."

The instrument chosen was the shakuhachi, Japan's "bamboo flute," an instrument with which Blasdel's name has now become synonymous. Very early on in his stay in Japan, intent upon the pursuit of the pattern, he was so fortunate to find the perfect teacher, Goro Yamaguchi, a master later to earn the prestigious title of "Living National Treasure." It was comparable "to a young Japanese going to New York to study piano and, without any knowledge or particular qualifications, receiving an introduction to a great performer like Artur Rubinstein."

Among the many things Blasdel learned in these early years was the reverence given to form in Japan. He learned that "form does not follow content; one must first consecrate oneself to the form -- through years of discipline -- and only then can content be allowed."

Form is learned through the practicing of kata, the structural support for most of the arts of Japan -- from the art of the shakuhachi through the arts of calligraphy, aikido, and much else. These kata at the same time "foster growth and provide a vessel for tempering one's abilities." And when they are truly mastered they become a tool to express content. As Blasdel learned: "Traditional forms of music can be negated only after they are fully internalized, and this take years of practice and discipline."

Blasdel's years of study under Yamaguchi were rewarded by both a mastery of his instrument and a professional name. All of Yamaguchi's students were given the Japanese character mei, meaning "alliance," taken from the shakuhachi guild name, and were then allowed a character of their own choosing. Blasdel chose yoh meaning, "from afar," and the completed professional name he was given was Yohmei.

His choosing to emphasize his distant origins had many reasons. One, certainly, was to suggest the lifelong search for form in the country where he was to spend his adult life. Among the others was the fact that "as a non-native one is able to acquire aspects of a culture while maintaining a detached objectivity." This was something he learned from another treasured teacher, the late Fumio Koizumi, who pointed out that an outsider can objectify and discern aspects of Japanese music that insiders cannot see. "The secret, he said, is to internalize, or subjectify, the shakuhachi yet remain detached from it."

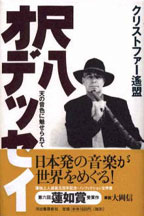

It is this discovery that has resulted in this valuable and interesting book that Blasdel wrote, originally, in Japanese. Titled "Shakuhachi Odessey," it was published in 2000 by Kawade Shobo and went on to win the prestigious Ren'nyo Award. The author later translated it into English and this handsome new volume has just this month appeared.

I don't know of any other book quite like it. It is both an autobiography and a guidebook, both the coming-of-age of an expatriate and a study of Japanese music. It contains an informed account of the history of the shakuhachi and at the same time personal reminiscences of those by whom the young Texan was befriended (such as the sculptor Isamu Noguchi).

It is also an extended commentary on the international growth of Japanese music: "I teach around the world, and find myself in the unusual position of helping to transmit Japan's traditional culture to both Japanese and non-Japanese students." Blasdel has learned that "at a certain point the distinction between 'us' and 'them' disappears, and all that matters is the music: the wheel comes around and we discover we are in the world together, regardless of nationality."

Riley Le's Review of The Single Tone

(Linked Version includes sound files)

Ethnomusicology

OnLine - Issue #9 (2005)

For the disadvantaged, non-Japanese-reading

members of the international shakuhachi community, the five years between

the publication

of Chris Blasdel’s original Shakuhachi Odessei in Japanese (Shakuhachi

Odyssey) and that of the English version, The Single Tone, seemed like a very

long time. It was worth the wait.

Shakuhachi Odessei was first published in 2000. The original book won the 6th

Japanese literature Ren’nyo Award for non-fiction in that year. The Ren’nyo

Award was established in 1994 to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the death

of Ren’nyo (1415-99), an important Jôdo Shinshû (New Pure

Land) priest who reinvigorated the sect in the 15th Century.

First prize for the Ren’nyo Award is ¥2,000,000 or approximately US$20,000.

A literary award of this magnitude in itself tends to attract considerable media attention in Japan. When the winner is a gaijin, a non-Japanese, the award becomes an even greater media event than usual. This is good news for shakuhachi players both in Japan and elsewhere; the shakuhachi needs the positive publicity.

In this sense, Blasdel has contributed to the health of the shakuhachi community in three ways, firstly by writing about the shakuhachi in a manner that appeals to more than just other Japanese literate shakuhachi players, then by winning a major Japanese literary prize, thus insuring a much wider readership in Japan than it would have otherwise, and finally, by translating the book into English.

In the preface, the author explains

that the original book, Shakuhachi Odessei is both an autobiography and a ‘guidebook’ of

the world of Japanese music (Blasdel 2005:viii). Tanaka Takafumi, the editor

of the popular Japanese

monthly magazine Hôgaku Journal once told me that the world of

traditional Japanese music (hôgaku no sekai) was as foreign to

most Japanese as foreign countries would be, with its own social rules,

customs, and

even language (personal

communication 1986).

In the preface, the author explains

that the original book, Shakuhachi Odessei is both an autobiography and a ‘guidebook’ of

the world of Japanese music (Blasdel 2005:viii). Tanaka Takafumi, the editor

of the popular Japanese

monthly magazine Hôgaku Journal once told me that the world of

traditional Japanese music (hôgaku no sekai) was as foreign to

most Japanese as foreign countries would be, with its own social rules,

customs, and

even language (personal

communication 1986).

Though Mr. Tanaka might have been exaggerating, his statement still makes the point that the need for a guidebook about Japanese music, written in Japanese for Japanese is not as far-fetched an idea as it might sound. That it took a non-Japanese to write such a guidebook on the shakuhachi is both ironic and indicative of the need for one.

To his credit, Blasdel saw the need for this sort of ‘guidebook’ and, more importantly, he has acquired both the intimate knowledge of hôgaku no sekai and the Japanese language skills to be able to write it. Though much of the book is autobiographical and may be only indirectly about the shakuhachi or traditional Japanese music, Blasel’s experiences make noteworthy reading for anyone interested in the workings of modern Japanese society.

The title, The Single Tone, will remind most shakuhachi players of the saying, Ichi on jôbutsu (One sound, becoming Buddha), an acknowledgment of the claim that enlightenment can be attained through one sound, including a single note on the shakuhachi. Blasdel’s title is, in fact, taken from a poem called Gratitude: by noted American poet, Sam Hamill (Blasdel 2005:v)

Play a single tone,

And reveal the truth therein.

The heart is a gate

Only the breath passes through—

Emptiness to emptiness

The Single Tone is a collection of personal and historical stories told in a way that guides the reader through many different ‘worlds’ within Japanese society. In addition to hôgaku no sekai, mentioned above, there is the bureaucratic world of the Tokyo government, the worlds of Japanese secondary and tertiary education and the contradictory world of the non-Japanese who is a long term resident of Japan, very much an insider but forever the outsider.

Blasdel’s journey is not however, confined to Japan. He takes his shakuhachi and the reader to isolated villages in the mountains of Guatemala, banquets in China and Central Europe, jungles in Argentina, concert halls in Hamburg, a school in Georgia SSR, and a pueblo in New Mexico.

Blasdel sets the personal tone

of the book in chapter one, by relating the story of how he first met, through

his shakuhachi

performance,

and eventually

became friends with the famous sculptor, Isamu Noguchi.

The choice

of beginning the book with his meeting with Noguchi, rather

than any number

of other

famous people with whom he has met, is deliberate. Noguchi,

we are told, empathizes

with Blasdel’s growing disquiet of belonging neither

to his adopted culture (Japan) nor the culture in which

he grew up (the panhandle

of Texas). Noguchi's

advice to Blasdel was that this state of not belonging

is a difficult one, but that it can also be a source of

strength.

Blasdel sets the personal tone

of the book in chapter one, by relating the story of how he first met, through

his shakuhachi

performance,

and eventually

became friends with the famous sculptor, Isamu Noguchi.

The choice

of beginning the book with his meeting with Noguchi, rather

than any number

of other

famous people with whom he has met, is deliberate. Noguchi,

we are told, empathizes

with Blasdel’s growing disquiet of belonging neither

to his adopted culture (Japan) nor the culture in which

he grew up (the panhandle

of Texas). Noguchi's

advice to Blasdel was that this state of not belonging

is a difficult one, but that it can also be a source of

strength.

Blasdel returns to the insider/outsider discussion periodically throughout the book. The emphasis given to this dichotomy is not merely an expression of the author’s personal problem. An entire chapter of my PhD dissertation (Lee 1992), was devoted to this issue, because,

… the concept of the ‘insider’ versus the ‘outsider’ plays a pervasive role within the shakuhachi tradition. It is likely that the primary motivation many shakuhachi players in Japan have in learning to play the instrument…is the desire to identify with and be loyal to other members of the traditions as insiders (see Nakane 1970; Dore 1958:387, Vogel 1968:147-158). (Lee 1992:15-16)

In my experience, how successfully one is able to define one’s own status within the ‘insider/outsider’ dichotomy, and also how one deals with, emotionally, psychologically and tangibly, the ever-changing and arbitrary status imposed upon one by ‘insiders’, will determine to a large degree one’s success as a shakuhachi player, or any other practitioner of traditional Japanese musical instruments.

The importance of this classification is further reflected in my decision to classify my dissertation’s required survey of the literature into four categories (Lee 1992:25):

1) literature written by insiders to the tradition for other insiders to the tradition

2) literature written by insiders to the tradition, but addressed to people who do not belong to the tradition

3) literature written by outsiders to the tradition aimed primarily at insiders to the tradition

4) literature written by outsiders to the tradition for other outsiders.

Blasdel’s book is successful in part because of the difficulty of pigeonholing it within a single category in the list above.

Isamu

Noguchi is the first of many people that Blasdel portrays in the stories

of his odyssey.

The most

influential person

to figure in these

stories is

Blasdel’s

shakuhachi teacher, Living National Treasure Yamaguchi

Gorô (1933-1999).

It is through Yamaguchi and his associates that

Blasdel learns his art of shakuhachi playing, much

of his understanding and appreciation

of his adopted home, and

ultimately about himself.

Isamu

Noguchi is the first of many people that Blasdel portrays in the stories

of his odyssey.

The most

influential person

to figure in these

stories is

Blasdel’s

shakuhachi teacher, Living National Treasure Yamaguchi

Gorô (1933-1999).

It is through Yamaguchi and his associates that

Blasdel learns his art of shakuhachi playing, much

of his understanding and appreciation

of his adopted home, and

ultimately about himself.

Blasdel describes his first and subsequent lessons with Yamaguchi at his home as if they were yesterday, even though many of them occurred decades ago. Yamaguchi conveyed an exceptionally calm ambience, which pervaded his lessons and his music.

Ironically, Blasdel is

not unique in the initial frustration that

he experienced with Yamaguchi’s largely

non-verbal and frequently form-oriented, mode

of teaching. Blasdel’s descriptions of

his close relationship with Yamaguchi, spanning

over three decades, was for this reader one of

the

most rewarding parts

of the book.

This relationship is evident in Blasdel’s shakuhachi performance

as well as in his book. It is not surprising to hear Yamaguchi’s

influence from the very first phrases of any of Blasdel’s recordings

of traditional Kinko honkyoku.

The spirit of Yamaguchi's playing is also apparent however, in Blasdel's frequent performances of the many modern pieces for which he is known, even though it is assumed that most if not all were self-taught.

Chapter

two is a brief account of the fictional and factual origins of the shakuhachi.

This chapter is

particularly

significant for

both its

Japanese and non-Japanese

readers, as both are, generally speaking,

equally ignorant of the genesis, fictional

and factual,

of the shakuhachi.

The historical

context of

the shakuhachi

is especially

important in understanding its repertoire

and its culture, in part

because of its widely publicised and

frequently misunderstood and/or misrepresented

association

with Zen Buddhism.

Chapter

two is a brief account of the fictional and factual origins of the shakuhachi.

This chapter is

particularly

significant for

both its

Japanese and non-Japanese

readers, as both are, generally speaking,

equally ignorant of the genesis, fictional

and factual,

of the shakuhachi.

The historical

context of

the shakuhachi

is especially

important in understanding its repertoire

and its culture, in part

because of its widely publicised and

frequently misunderstood and/or misrepresented

association

with Zen Buddhism.

Parts of The Single Tone reflect its having been written initially for a Japanese readership. The woefully inadequate teaching of traditional Japanese music in Japan’s public school system is mildly interesting to the non-Japanese reader, but other stories related to the shakuhachi might have been more captivating, for example, visits to shakuhachi makers, or how shakuhachi players make a living in today’s Japan.

Blasdel has been immersed in the shakuhachi tradition in Japan at its deepest and most traditional level for over thirty years, performing, recording and teaching.

The Single Tone is not a journal of mainly first impressions of a newcomer to the scene, or an informative travel book with a focus on the shakuhachi. However entertaining, well researched and perceptive these kinds of books may be, they are written by outsiders for a readership who are for the most part also outsiders.

In contrast, Blasdel tells a series of stories, both personal and historical, from an insider’s perspective, but in a way that can be appreciated by both insiders and outsiders, and on a number of different levels. The tension and the perceptions experienced and eloquently expressed by Blasdel, from being both ‘insider’ to the world of the shakuhachi and forever ‘outsider’ to Japanese society is, as Noguchi predicted, the strength of this book.

----------

References Cited

Dore, R.P.

1958 City Life in Japan, Berkeley: University of California Press

Lee, Riley

1992 Yearning for the Bell: a study of transmission in the shakuhachi honkyoku

tradition, Unpublished PhD dissertation (University of Sydney)

Nakane, Chie

1970 Japanese Society, Suffolk: The Chaucer Press

Vogel, Ezra F.

1968 Japan's New Middle Class; the Salary Man and his Family in a Tokyo

Suburb, Berkeley: University of California Press

----------

Riley Lee began shakuhachi in Japan in 1970, and began wadaiko in 1973 with the group now called Kodô. In 1980, he became the first non-Japanese shakuhachi dai shihan (Grand Master). He studied with Sakai Chikuho II and with Yokoyama Katsuya. Riley has a PhD (ethnomusicology, University of Sydney 1992), and a MA and BA (ethnomusicology, University of Hawai'i 1986 and 1983). He performs, teaches and lectures extensively worldwide and has released over 50 recordings. In April 2005, he premiered Australian composer Ross Edward’s shakuhachi concerto, “The Heart of Night” with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra.

THE SHAKUHACHI: A Manual for Learning Recorded Music THE ZEN MIND Video |

| Price of Book | Ordering Information |