Karhu of Kyoto

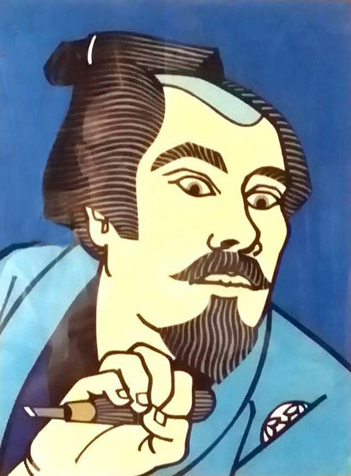

Clifton Karhu, a Former American Missionary, Has Become One of Japan’s Most Famous Artists

—to Some, ‘More Japanese Than a Japanese

By Andrew Horvat Aug. 24, 1986 Los Angeles Times

Japan’s most popular practitioner of the 700-year-old craft of woodblock printing sweeps the wide sleeves of his kimono to one side and gently pushes the blade of a curved chisel into a slab of linden. With the tool, which he made by hand, the artist slowly begins carving the mirror image of an old gate in Kyoto, Japan’s former capital.

A 25-year resident of the ancient city, he is renowned for his defense of Japanese traditions. He has spoken out publicly against the destruction of Kyoto’s wooden architecture--the subject of his acclaimed prints--and he continues to argue the superiority of thongs over shoes, sake over whiskey, and raw fish over cooked meat. He is proud to own not a single item of Western-style clothing.

Yet, this acknowledged master of a most thoroughly Japanese art form is not himself Japanese. He is Clifton Karhu, a blond American of Scandinavian descent, formerly of Duluth, Minn., who came to Japan 31 years ago as a Protestant missionary hoping to introduce the values of an alien religion.

Today he is described in the Japanese news media as “more Japanese than a Japanese” and, in a curious twist, has become perhaps the best-known defender of tradition in an artistic culture busily trying to keep up with Western innovation. He is criticized as an artistic throwback but has been credited with redefining and reinvigorating an ancient printing technique. He is sometimes dismissed as a mere postcard painter, popular only with Western tourists; yet his prints are widely purchased by ordinary Japanese, who find his style easy to understand.

Since his transformation from missionary to artist a quarter-century ago, Karhu (his last name is Finnish, although it is sometimes mistaken for Japanese) has made 700 prints in issues of about 100 each. He has taken part in more than 200 exhibitions and has accepted well over 250 commissions for works. Matsushita Electric, manufacturer of Quasar television sets and Panasonic appliances, is but one of dozens of major Japanese corporations to have used Karhu prints on their calendars. Demand for Karhu’s works is so high that he even has to contend with a Japanese imitator who sells Karhu look-alikes in Kyoto’s cheaper galleries.

Yasuhiko Okamoto, scion of a family that has been in the restaurant business in Kyoto for four generations, says he and his father chose 28 Karhus to hang on the walls of their Yagenbori (Spice Grinder) restaurants because “we were looking for something traditional.”

“There is not a day that some customer does not ask about Mr. Karhu’s pictures,” Okamoto says. “Of course, they are shocked to hear that the artist is not Japanese. We explain to our customers that Mr. Karhu comes here to eat and drink, and that he knows Japanese food as well as any of us.”

Eating at the restaurant recently, Karhu enjoyed a meal of one small river fish, sliced live and eaten while still quivering; raw horse meat, and plenty of sake.

The mirror image of the wooden gate is nearly finished. It started as a rough sketch of the gate outside Karhu’s studio, turned into a neat drawing with the heavy black lines that characterize a Karhu print, and then, pasted on a slab of linden, formed the first plate of the print--the so-called skeleton block.

Carving away everything except the lines on the skeleton block, Karhu will print six identical black-and-white preliminary images. Those he will paste on six other blocks, one for each color. As colors often overlap or just barely border on one another, chiseling is exacting work. The process involves about 30 steps, from initial sketch to the final tense moment when the artist rubs the back of the moistened mulberry paper and lifts it to see whether all the colors fit.

For his print of the gate, Karhu has decided to use only blue--six shades of it: “It’s summer. Blue is nice and cool.” But there is another reason. Karhu, an expert on the history of woodblocks, explains that in the late 17th Century, authorities cracked down on what they perceived to be luxurious living by townspeople and banned the use of all colors but blue. Karhu is harking back to that period.

While other Japanese printmakers adopted such Western techniques as lithography, copper engraving and silk-screen printing and have turned to abstract subjects, Karhu is more closely rooted in the now-defunct but long-popular tradition of ukiyo-e , or “floating world,” prints. The ukiyo-e derived their name from their subjects: scenes of entertainment districts, and the generally short lives and fleeting pleasures found there.

“There have been others before him who have done pictures of famous temples and palaces,” says Tokio Miyashita, a fellow printmaker, “but Karhu is basically alone in concentrating on the buildings where ordinary Japanese spend their lives.”

There is little doubt that a Japanese viewing a Karhu picture is struck by a sense of nostalgia. A Karhu print of Kyoto’s bustling Gion entertainment district contains no people in modern clothes, no cars, no telephone poles and no garish posters advertising cabarets or strip shows. If a human happens to intrude on a Karhu scene, chances are it will be a geisha, wearing a kimono. And if a Karhu character does leave something outside her house, it will be a bamboo-and-silk parasol, not an umbrella, and a pair of wooden clogs, not leather shoes.

Karhu also cites historical precedent to justify his use of strong, primary colors in his prints. “It is a common mistake to assume that old Japanese prints were more understated in their use of colors than later ones, or that the Japanese print as art was destroyed with the advent of Western dyes,” he says. “The old prints, too, were gaudy. It is just that the dyes used in them have faded with age.”

Karhu has maintained continuity with the past even in the way he sells his works. He insists on releasing his prints in issues of 100, or roughly four times the normal number for an art print in Japan. Ukiyo-e publishers used to print from their blocks for as long as they could get a clear image. Stressing that his is a democratic art form, Karhu says, “A print should be cheap enough so that you don’t have to ask your wife whether you can buy one.”

The philosophy has brought him criticism from Japan’s artistic avant-garde. “Karhu’s technique is excellent, but it is essentially decorative,” says Tetsuya Noda, a prize-winning print artist who combines photographic processes with woodblock printing. “When Americans get to like Japan, that’s the sort of pictures they make.” Hisae Fujii, curator of prints at Tokyo’s National Gallery of Modern Art, agrees: “Karhu’s pictures are good to look at when one is tired, but they do not stimulate us to look into the future.”

Even so, more than half of Karhu’s prints are bought by Japanese, in contrast to about 30% for other Japanese printmakers--a fact that Karhu uses to defend his basically representational style. “While abstract art grew up in America, abstract art in Japan grew out of imitating America,” he says. To him, abstract art in Japan is the equivalent of Western clothing or plastic and aluminum housing--unnatural.

“In the past, Japanese houses used to be made of wood and paper,” Karhu says in an enthusiastic, almost adolescent voice. “Now the basic ingredient is plastic. In one type of house there is an aluminum duct for toilet odors that is placed right next to the front entrance. I can’t say that I am inspired to do a picture of such a building.”

$28,000 white Toyota Soarer is one of the few compromises with modern civilization that Karhu is happy to make. The sports car, which is unavailable in America, has a color television set built into its instrument panel, allowing Karhu to enjoy his favorite afternoon soap operas even while he’s stuck in traffic. “I’m addicted to the stuff,” he says. (During an interview in his studio, he lifts his head from a particularly difficult print to see whether two soap-opera mothers have succeeded in getting their children into a prestigious private school by bribing the principal.)

Karhu navigates his Soarer through the narrow alleys of Kyoto’s Gion district to show a photographer the buildings that serve as inspiration for his prints. Returning a few days later with copies of Karhu’s work, the photographer gives up trying to locate all but a few of the artist’s subjects. Karhu hadn’t mentioned that he radically changes the shapes, designs and colors of almost every one of the buildings in his prints.

“Natural scenes are out of order,” Karhu says, “so the task of the artist is to re-establish order.” His sense of order, however, dictates that a print of Kyoto’s Heian Shrine, which is known to every Japanese schoolchild as having a bright red gate and a dull black roof, should be executed in purple, yellow, green and brown. A scene of a geisha slipping into a salon in a dark alley at dusk turns into a print of 10 colors, most of them bright.

In Karhu’s hands, square buildings become oblong, a persimmon tree laden with bright orange fruit materializes in front of his studio window, and a bland hotel room acquires wallpaper with a cherry-petal motif to match the flowers in bloom outside.

Karhu’s interest in Japan’s traditional ways does not stop with the woodblock print. In fact, it is unlikely that there is a Japanese anywhere today who compares with him in combining all the skills of Japan’s traditional arts.

He is an accomplished player of the shakuhachi , a five-holed bamboo flute used in folk and classical music. He enjoys a distinguished reputation as a carver of Oriental signature seals, which are a part of daily life in Japan and are considered a sign of sophistication. And he is proficient in written Japanese.

Karhu is also known to many of his Japanese fans for humorous paintings done in a style reminiscent of Japanese sumi-e-- charcoal ink pictures. Karhu decorates the paintings with Chinese and Japanese poetry. Recently, he did a series with Jewish sayings, translating the proverbs into Japanese.

Karhu has also put his paintings--usually depicting some frenzied-looking animal of the Chinese zodiac or a drunken god of happiness--on Kutani porcelain, a traditional Kyoto product. A large plate painted by Karhu sells for the equivalent of $2,800 at department store exhibitions.

He appears on television and in print regularly enough to be recognized on the street. In the bar of the Kyoto Royal Hotel, strangers wave at him, while at a restaurant, girls at the cash register giggle in their palms and ask if the blond giant in the flowing robes was the man on the terebi the week before.

One reason for his popularity as a media personality is his constant flow of humorous stories, which he delivers in a faintly accented Japanese. In one interview, he recalled his first days in a kimono. “One day I showed up at a bar, and the other customers were pointing at me and giggling,” he recalled. It turned out that Karhu, then a novice in Japan, had gone out on the town in the equivalent of a bathrobe.

He has, it seems, made up for whatever time he lost. He is a frequent visitor to the Gion, where Kyoto’s best geisha houses are located. Most of the houses have become little different from Western-style bars, but one holdover from the old days is that customers do not talk to each other unless they are formally introduced by the owner.

At a geisha house one night in July, the kimono-clad proprietress asked a neatly dressed gentleman at the bar if he knew Karhu.

“Do I know Mr. Karhu?” responded the man, a prefectural assembly member of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. “Mr. Karhu is famous. He is introducing our culture abroad and keeping our traditions alive at home. Mr. Karhu ought to be decorated for his efforts.”

“Me?” Karhu said. “I just sell pictures.”

I n contrast to a great number of expatriates living in Japan, Karhu insists that Japanese society is not exclusionist. Even so, it is difficult to understand how an American of Finnish descent, born in a small farm town in the Midwest in 1927, should end up, nearly 60 years later, living the life of a Japanese artist.

Karhu suggests that language has been the key: “It’s a lot easier to get to like sushi after you’ve learned to speak Japanese.” But clearly there is more. A hint of his motivation comes in an epigram on one of his charcoal-ink paintings. The saying reads: “You do best what you like to do.”

Karhu came to that realization relatively late in life, amid failure in an isolated Japanese mountain community and in poverty unimaginable for an American in Japan.

For most of his early years, he had vacillated between a love of painting and religiosity, both instilled by his parents. “I was having too much fun as an artist,” Karhu says of his days as an art student in Minneapolis in the early 1950s. “I had come to think that artists were people who pursued their pleasures with rich people’s money.”

Overcome by feelings of guilt, he quit his painting classes and enrolled in Bible school. He was ordained a Lutheran minister in 1955 and became such an enthusiastic missionary that during his prime he was selling as many as 60 Bibles a day from door to door in Hiroshima.

“Then one day I met a banker to whom I had sold a Bible, and he told me that he understood the Bible very well but that the book of explanations that came with it had puzzled him,” Karhu says. The incident triggered a new round of doubt in Karhu. “Everywhere there were rules,” he says.

Karhu came to resent being what he calls a “professional missionary” and moved his wife and two children to Gifu City, a provincial town in a mountainous area northwest of Kyoto. Cut off financially from his mission, the family was living on the equivalent of $38 per month, mostly from teaching English. They owed much of their intake of protein to the lack of refrigeration in rural Japan in the late 1950s: “We’d get old milk from the dairy farms,” his wife, Lois, recalls, “and I made cheese out of it.”

Things got better, Karhu says, “after I stopped crying and started fishing.” He also went back to painting and in 1961 won a major local prize for his watercolors. The following year he was exhibiting in Tokyo. A year later, he had mastered the art of woodblock printing and obtained membership in the prestigious Japan Print Assn.

This phenomenal rise in fortune started in the home of a Gifu City doctor to whom Karhu had been teaching English. The doctor introduced Karhu to Tamotsu Hattori, an oil painter, who helped Karhu stage a one-man show. “The rent for the gallery, $8 per day, almost bankrupted me,” Karhu says, and Hattori had to ask a local art-supply shop to lend him frames for the show. Hattori himself was so hard up that he rented his oils to coffee shops for the equivalent of 33 cents per picture per month.

Karhu was still teaching English and painting as a sideline in 1961 when he again moved his family, this time to Kyoto so that his eldest son--who had appalled his parents by beginning to speak English with a Japanese accent--could attend an international school. In Kyoto, Karhu met gallery owner and woodblock print artist Tetsuo Yamada, who not only took him in as a pupil in woodblock carving but also introduced him to Stanton Macdonald-Wright, a California painter who was to have a profound influence on Karhu.

Wright, who once described himself as having been “expelled from a variety of Los Angeles schools,” turned up in Paris in 1913 at the age of 23, exhibiting wildly colored abstracts. Ten years later, he published his theory of color harmony and then mysteriously retired from exhibiting for 30 years. In the 1960s, he divided his time between Los Angeles and a room in Kenninji, a 12th-Century Zen monastery in Kyoto.

“Wright was a meticulous painter,” Yamada says. “He would squeeze his colors out on a glass table, and his picture was finished exactly when the paint on the table had run out. He never added an extra drop.”

Wright first taught Karhu his theory, which likened colors to notes on a musical scale and color combinations to chords. But then, just as a Zen priest might have told an acolyte, he warned Karhu that “there are no rules.” When Karhu, still suffering from his doubts about the value of the artist in society, expressed those concerns one day, Wright angrily proclaimed: “Artists are gods. They alone create. Everything that brings pleasure to people’s lives was made by an artist.”

Karhu’s artistic transformation was complete.

His other transformation--into Japanese society--includes his family as well. Although Lois does not wear kimonos, she has adopted the traditional Japanese wife’s role of handling family finances and is Karhu’s secretary, manager and impresario. Their eldest son works for a Japanese conglomerate, and their youngest devotes most of his spare time to taking care of six four-cylinder motorcycles--all of them Japanese.

Karhu and Hattori still keep in touch. At the plush Osaka gallery in which Hattori exhibits his latest oils of Spanish and French rural scenes, he spreads out a large sheet of mulberry paper he has received from his student. At the beginning of the letter is a phrase written with the bold brush strokes that Karhu learned while studying charcoal ink painting in Gifu. It reads: “Live for the moment.”

T hough unperturbed by the cold shoulder of Japan’s artistic elite, Karhu is upset by the work of one Japanese printmaker, Katsuyuki Nishijima. For years now, Nishijima has been making prints of old Kyoto houses in bright colors. Like Karhu’s prints, Nishijima’s have no people in them. Occasionally they will contain a few colorful parasols.

A Nishijima print, which he signs in capital letters, like Karhu, sells for about $35, or nearly one-third the price of a Karhu print. “They come in limited editions of 500,” Karhu says with a smile.

Norman Tolman, a former Foreign Service officer who is now Karhu’s main dealer, calls them “rip-offs.” Printmaker Miyashita has condemned them as copies but says, “Legally, of course, it is difficult to tell just what constitutes a copy.”

Nishijima adamantly denies copying Karhu. “Mr. Karhu was brought up eating steak, and I ate rice as a child,” he says, “so our work cannot look the same.”

But Miyashita says otherwise. The real reason Nishijima has been able to sell his Karhu look-alikes to galleries in Kyoto, he says, is because “Mr. Karhu is too much of a Japanese. He is loyal to those who helped him on his way up.” Thus, because Karhu for years has given the bulk of his production to his former teacher, Yamada, many rival galleries have turned to look-alikes to compete.

Nishijima, however, has paid a high price for his lack of originality. He has been effectively denied membership in the Japan Print Assn., while Karhu was elected head of the society’s Kyoto Chapter.

In his home country, too, Karhu is becoming recognized. Earlier this year, banker and art collector David Rockefeller bought a number of Karhus through the gallery, as did the Cincinnati Museum. Last April, U.S. Defense Secretary Caspar W. Weinberger, who had received a Karhu print from the head of Japan’s Defense Agency, diverted his motorcade to Tolman’s gallery near Tokyo’s Zojoji Temple to pick out a small Karhu for himself.

This summer, Karhu returned to Minnesota to attend the opening of a retrospective of his work at the University of Minnesota’s Tweed Museum in Duluth. Uncompromising as always, he wore only kimonos. Stares followed him everywhere.

“In Japan I am an American, and in the United States I am a Japanese,” Karhu sighed. “I decided a long time ago that the only answer is to be me.”